This fall Huis Marseille presents the exhibition Shadow Self – Portal to a Parallel World, with work by Shuang Li (1990), Charmaine Poh (1990), Heesoo Kwon (1990), Xiaopeng Yuan (1987), and Diane Severin Nguyen (1990). ‘Where does an image begin and where does it end?’ A question – and a responsibility – for contemporary artists who make use of new media and technologies such as generative AI. In Shadow Self five artists examine this crucial issue from a personal perspective.

Shadow Self chooses five artists whose work investigates parallel worlds from a personal or even autobiographical standpoint. The ‘shadow self’ that exists in these parallel worlds is not a black shadow escaped from the ghostly world of a fantasy novel, but an opening into imagination, a portal to a world populated by the spirits of human creativity. The image points the way to another dimension. What is it like to exist permanently on the internet as the 12-year-old child you once were, as happened to the artist Charmaine Poh? What happens when the ghosts of female ancestors suddenly appear in daily life, as in work by Heesoo Kwon? These are just two of the topics explored in the exhibition Shadow Self.

Physically absent, virtually present

A computer screen offered the Chinese artist Shuang Li (1990) her only access to the world outside the small industrial town in the Wuyi Mountains where she grew up. Her life changed when she discovered the American pop-punk/emo band My Chemical Romance, whose lyrics seemed to express her feelings perfectly. Shuang Li learned English through her activities on an internet fan forum, and ‘fandom’ subculture continues to form the base of her work, encompassing performance, sculpture, video, and an interactive website. In 2022, when Covid travel restrictions kept her in Europe, she sent twenty performers as her avatars to a gallery opening in Shanghai. They were dressed identically, in a My Chemical Romance t-shirt over a white shirt, a black blazer, a checkered skirt, black boots, legwarmers, and a silver-coloured backpack. At the opening they read out a personal message from Li to her friends, and their actions were recorded with The Matrix-like spy-cam glasses. The video that resulted from this performance, Déja Vu, reflects on Li’s fluid existence between different towns, during lockdowns and closed-border periods, when computer screens gave her a virtual presence despite her physical absence. In the second video in the exhibition, My Way Home Is through You (2023), Shuang Li links memories of her youth in China to the cover of a family photo album and its stock image of a Swiss castle, which she later discovered was actually a juvenile prison. Themes such as imprisonment and the ubiquity of stock images are combined with research into nostalgia, homesickness, feelings of confinement, and the blurring of distinctions between time and distance.

Back to childhood in the work of Charmaine Poh, Heesoo Kwon, and Chino Otsuka

It is remarkable how many contemporary artists are virtually resurrecting their childhoods in their work. In the early 2000s the Singapore-born Charmaine Poh (1990) was a child star actor in the television series We Are R.E.M. The experience forms the basis of her video GOOD MORNING YOUNG BODY (2023), in which the eternally 12-year-old character E-Ching is a deepfake derived from footage of Poh’s younger self found on the internet. In the video E-Ching responds to the public comments and scrutiny she was exposed to at the time. Charmaine Poh uses film, photography and performance to address the many issues surrounding virtual ownership. It also overlaps with her PhD research into the queer Asian body and its digital depiction.

Frustrated with the patriarchal Korean culture and Catholicism under which her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmothers lived, Korean artist Heesoo Kwon (1990) created ‘Leymusoom’, an autobiographical feminist religion. Drawing a connection to snakes shedding their old skin, she visualized Leymusoom as a fluid entity between snake and woman. Like a reptile, they shed their skin in a process of metamorphosis, reborn as queer bodies without the burden of previous lives and patriarchy. In lenticular prints that reimagine Kwon’s childhood family photographs, we see avatars of her female ancestors and Leymusoom, appear and disappear as patron gods. Kwon uses these avatars in her video works to blur boundaries between time and space, historicizing her matriarchal lineages while creating a communal digital world of introspection for the audience, avatar, and self. Beyond the lenticular image series, Kwon expands the physicality of and questions the veracity of memory within her own childhood photos by using composite techniques in Photoshop and the generative AI tool Adobe Firefly. Firefly acts as a collaborator and a therapist, helping the artist create holistic reconstructions of her childhood home — extending the original viewpoint of childhood photographs, adding surrounding furniture, and distorting the body parts of the pictured family members. In creating introspective fantasy worlds that re-historicize Korean history and the family archive, Kwon illuminates the invisible, allowing the artist to actualize the liberation of her ancestors and self from historical oppression rooted in patriarchy.

A pioneer in this sort of virtual time travel is the Japanese artist Chino Otsuka (1972), some of whose photographs are included in Huis Marseille’s own collection. Otsuka had an unusual childhood, because of the many journeys she made together with her parents. In the first decade of the 21st century she revisited as an adult the places she had been photographed as a child by her parents 25 years earlier, and created new photographic works that united her younger and older self in a single image.

The image as a portal

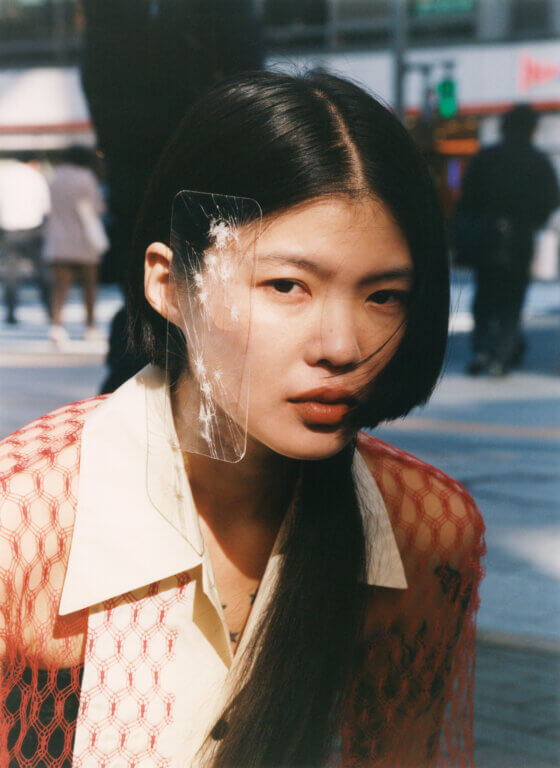

An image that is not virtual, but which has been created using an analogue or digital camera, may also function as a portal to an unfamiliar universe that gives the impression that it lies hidden behind the visible world. Within the context of commercial photoshoots the Chinese artist Xiaopeng Yuan (1987) creates new and unexpected stories through the manipulation of bodies and objects in space and in unlikely combinations. The pure, clean language of his fashion photography actually increases the suggestiveness of his images, as Yuan’s unusual combinations makes one think about the world outside the frame of the photo.

The Vietnamese-American artist Diane Severin Nguyen (1990) speaks of the ‘wounds’ and ‘ruptures’ in the image that she creates for the camera using unusual or disconcerting materials, with bright, fiery colours, and doused in sensual light. The camera records the image, and the act involves a certain degree of violence. The film Tyrant Star shown in the exhibition is full of saturated images that appear to conceal a mysterious, parallel life, one which an incision would reveal.

Featuring work from our collection by

Bownik, Kyungwoo Chun, Louisa Clement, Jamie Hawkesworth, Arja Hop & Peter Svenson, Nhu Xuan Hua, Naoya Ikegami, Juul Kraijer, Shuang Li, Yuki Onodera, Diane Severin Nguyen, Chino Otsuka, Frida Orupabo, Lieko Shiga, Yasumasa Morimura, Joscha Steffens, Simon van Til

Evenement

Eye on Art: Pixel Flesh Lecture with Nanda van den Berg, Heesoo Kwon and Charmaine Poh

More info