Huis Marseille opened its doors on 18 September 1999 with exhibitions of the French photo pioneer Albert Londe, photographs by the Dutch artist Daan van Golden, an installation in the garden by Rini Hurkmans and a selection from the collection.

Albert Londe, an experimental and versatile photographer

Six men in coat and top hat frozen in the midst of a funny caper: in this typical image from the early days of instant photography one recognises some of the jolly chaps brought together by Albert Londe and Gaston Tissandier in 1887 within the framework of the Travel Club of Amateur Photographers (Société d’excursions des amateurs photographes, SEAP). However, this shot was taken within the confines of Paris’ largest hospital, not far from professor Charcot’s ward for the neurotic and the insane. This is exactly where Londe, a little later, would photograph a hysteric woman who ‘rips through the tethers of her straitjacket in a fit of insanity and, unhampered by a fractured foot which normally keeps her bedridden, escapes into the gardens of the Salpêtrière Hospital’.

Although the rudeness of the contrast between the crippled flight of the hysteric woman and the capriole of the amateur photographers was probably not obvious to Londe. It allowed him to get away with this recreational shot despite the rigid routine of his official duties. It as well conveys the essence of his contribution to the photography of the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Whereas in the literature of those days his name was frequently mentioned in the same breath with those of famous scholars such as Jules Janssen and Étienne-Jules Marey, who used photographic techniques for scientific analysis, Londe actually represents the antithesis: a tourist in the realm of technology who puts science to work for the benefit of photography. In the French tradition of the medium, it is he who transposes the experimental achievements of chronophotography into the vocabulary of amateur practice. In this respect, he may well be considered one of the inventors of instant photography as a genre.

Taken on by Jean-Martin Charcot as a chemical assistant in 1882, Londe immediately offered his services as a ‘picture maker’. Doctor Bourneville, the driving force behind the first Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière, left the hospital in 1879. Even though Charcot appealed first to Loreau, assistant in the hospital’s department of anatomic wax models and occasional photographer, he was soon won over by the competence of the young Londe, a specialist in the dry-plate process. Thanks to his invention of the mechanical shutter, Londe made Charcot aware of the importance of the new emulsion that seemed so auspicious for medical iconography. Professor Charcot had recently embarked upon his latest field of study: male hysteria. In May 1882 the negatives of the Brodsky case provided the first attested example of the use of photography in the illustration of his courses.

Londe, who was a member of the French Association of Photography (Société française de la photographie, SFP) since 1879, was devoted to the new ideology of the medium propagated by its president Alphonse Davanne, who strove for the recognition of the sensitive plate as a means of scientific inquiry. At that time, there were relatively few examples to back up this application, which he hoped to promote as a counterbalance to the generally negative image of photography. When he arrived at the Salpêtrière Hospital, Londe was already excited by the prospect of coming up with a clinical use for photography, which he was to defend at all costs. Copying his approach from the rules of medical observation, he effected a systematic reorganisation of the former photo atelier, to make it the equivalent of an autonomous hospital service provided with its own protocols and specially developed equipment. Marey’s Physiological Laboratory created in 1882 served as a model for what a laboratory of photographic research could be, and it is no surprise that as of 1883 one sees Londe resort to the method of sequential registration promoted by the famous physiologist. When modifying one of his stereoscopic shutters, Londe provided it with an electric release system – and immediately saw his camera being praised in the columns of La Nature and mentioned in numerous publications.

Yet, despite Londe’s insistence on bringing its strictly medical applications to the fore, the camera with nine lenses had been conceived to cope with a wide range of circumstances. Unlike the equipment used by Muybridge or Marey, which impose a specific shooting scenography, and unlike the first images of chronophotography — simple, flat silhouettes against a white or black background — Londe’s camera could be used in many ways. It produced negatives that were real photographs by virtue of their shape and depth. It was the first apparatus for sequential registration realised after the example of a random photo camera. Conceived in the environment of the Salpêtrière Hospital and with a scientific objective, the camera was not to be used much for medical research. Among the images that have been preserved to this day, only a few sequences for medical purposes remain. On the other hand, there are more numerous negatives that testify to non-scientific photo sessions, such as the ‘animated’ portrait of Mademoiselle Charcot or the photograph of a horse that had fallen in the water.

Within a few years, the photographic services of the Salpêtrière Hospital were seen as a model of the genre in Europe. Numerous physicians, interns and students used the rich documentation that had been collected. Also Londe’s assistance was often requested in capturing the most remarkable cases. Within the margins of his work at the hospital, Londe also opened the doors of his atelier to amateur photographers in pursuit of advice and photography lessons. His laboratory soon became the haunt of a circle of faithful followers, including Paul Boisard, Guy de la Bretonnière, Maurice Bucquet, Charles Dessoudeix, Jacques Ducom, Maurice Guibert, Georges Masson, Achille Mermet, Albert and Gaston Tissandier and Étienne Wallon. The author of many writings and of numerous lectures aimed at sharing a body of knowledge that had been patiently acquired, Londe was an inexhaustible educator in the field of photography who, when addressing the amateur photographers, never stopped insisting that: ‘Vae solis! Woe to those who work alone! Form a group, pool your efforts, in the first place in your own interest, as well as in the interest of photography, which counts on you to keep it on the road of progress’. In May 1887 he spirited his friends off on a photographic excursion to the quarries of Argenteuil: et voila, the Travel Club of Amateur Photographers was born. Its aim would be to pursue the method of ‘mutual learning’ developed at the Salpêtrière Hospital, but this time on a larger scale.

From the hippodrome of Paris to the observatory of Meudon, the military school of Joinville-le-Pont to the racetracks at Chantilly, the forest of Fontainebleau, or to the banks of the Marne, an excursion in the spirit of SEAP rigorously conveyed the new exercise in curiosity made possible by the dry-plate process. A dry process that was easy to use while on excursion, it was also more sensitive than the old wet collodion process and brought instant photography within reach. Widely popularised by the publications of those days, the initial scientific applications of this new support medium showed that, for the first time, the sensitive plate could capture phenomena invisible to the naked eye. Strongly influenced by this example, the amateur photographers of the years 1880-1890 no longer saw photography as a neutral form of recording the world around them. By virtue of its ability to capture a passing moment, frame a particular image, and reveal a hidden world by freezing it in motion, photography was henceforth perceived as having something to teach about reality. It became a tool for seeing the world anew, an instrument for reading and deciphering the visible. As an exercise in discovering and recording unprecedented subjects for posterity, the photos taken by the excursionists foretold and ushered in the dawning practice of photojournalism.

Despite the fame he attained with his work at the Salpêtrière Hospital, Londe did not receive the financial support that would have allowed him to develop his research. The realisation of his chronophotography camera with twelve lenses, presented in 1893, was only possible due to a personal contribution. That same year, when his work was crowned by the publication of La Photographie médicale, he also faced the death of Charcot – his patron in the hospital environment. Embittered and disheartened, Londe was planning to interrupt his activities. The discovery of X-rays in 1895 temporarily swayed him from this decision. Excited by Röntgen’s invention, he installed at his own expense the first X-ray laboratory of the Parisian hospitals and then received a grant allowing him to set up a fully-equipped radiology department for which he obtained high praise from the radiologist Antoine Béclère. However, the medical authorities soon took control of this application and it again slipped away from the photographer’s intentions. As of 1900, Londe delegated the greater part of his duties to his assistant Charles Infroit, who was to succeed him officially in 1903. As he spent more and more time away from Paris, Londe dedicated himself to his personal investigations, such as the analysis of artificial lighting.

In those early days of the twentieth century the popularisation of photography, which Londe had passionately advocated, had now been achieved. But the photographer could not identify with the new generation of amateur photographers, who had become merely users of a technology that they did not grasp. Far from giving access to the exacting practice of the medium claimed by the founder of the SEAP, photography had become a random pastime for the general public. In reaction to this press-of-a-button downward trend, the aesthetic principles, which had been developed by the supporters of Pictorialism within the photo clubs who advocated manual intervention in the printing process, drifted even further away from Londe’s and Davanne’s conception of photography as an expression of ‘truth’. Until he retreated to Rueil-en-Brie, Londe remained truthful to these ‘ethics of the image’, which he had helped to establish and that he still rendered in his last autochromes.

Daan van Golden, Artist-Photographer

To Daan van Golden (1936), art and life are intricately linked. His foremost source of inspiration is what he sees and experiences around him, be it at home in Schiedam or on one of his many journeys to exotic locations. With a sharp eye for details, he is able to capture images that are everyday and yet distinctive. In the catalogue of Van Golden’s current exhibition in the Dutch pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Karel Schampers, curator of modern art at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, aptly describes Van Golden’s work as ‘a continuous search for the wonder of ‘seeing’’. Fittingly enough, the catalogue is called The Pencil of Nature, which neatly captures his outlook on art. At the same time, the title harks back to the pioneers of photography, whose uninhibited perception of nature and their surroundings Van Golden shares. The invention of photography in 1839 brought with it a whole new conception of reality. Artists, scientists and adventurers embarked on voyages of discovery to investigate the new imaging possibilities of the camera – the pencil of nature. The original book The Pencil of Nature was published in 1844 by William Henry Fox Talbot (1800‑1877), the British inventor of photography. It is not only the first account of this voyage of discovery, but also the very first publication to be illustrated with photographs. The subject matter of the photographs varies from places and buildings that were important to Talbot to carefully composed still lives. His wife and children also represented a constant source of inspiration. He worked with the same concentrated attention to his subjects as Van Golden would do a century and a half later. In this respect, the nineteenth‑century scientist and the twentieth‑century artist share a common desire to investigate the possibilities of the medium using, as it were, the dormant images immediately around them.

Daan van Golden incorporates the ‘fantastic’ that crosses his path into his work in different ways. Photography is just one of the techniques at his disposal for capturing the visual reality that surrounds him. It was not until the mid‑1960’s that the medium became part of his very diverse body of work, which had previously consisted of paintings, collages, and silk‑screen and other prints. His first photographs were conceptual pieces in which the idea behind the image was more important than the quality of the image itself. They were mostly intended for publication, exhibition catalogues and magazines such as Museumjournaal, which published various photographs. In 1967, Van Golden lived in London with his then‑girlfriend Willy van Rooy. His pictures of Willy, who had just embarked on a career as a photo model, appeared in publications such as Vogue. It brought him to a more serious use of the photographic technique, in that he began to use photography for individual works of art. The medium offered him a certain degree of freedom in the determination of the subject and composition, in which chance played an increasingly important role. But what is chance still for a trained eye as Van Golden’s? Nevertheless, Van Golden’s early use of photography in his work displayed strong similarities with the formalistic realisation of his illusionary paintings of wrapping paper, handkerchiefs and tablecloths. Both forms have a structure that is derived from rasters, frames and patterns. Thus he would enlarge newspaper photos of Mick Jagger and Fats Domino to make the raster – the division of the image into dots – clearly visible. He would then paint an extremely accurate copy of the picture or incorporate it into large silk‑screen prints. The picture of Willy in furs on the Welsh coast, which forms the basis for ‘Wales Picture’ is also enlarged and divided in a pattern of 56 small golden frames. Not just the raster but also the spaces in between contribute to the visual tension of the image.

Apart from his own photographs, Van Golden also makes extensive use of other, mostly anonymous material that he re‑photographs, minutely copies with a brush or incorporates into his collages. This modus operandi – the reuse of material – expresses on a general level his opinions on the creation of works of art. To him, art is not static but in a constant state of change in both meaning and form. Whether it be handkerchiefs or photos of Brigitte Bardot, in Van Golden’s works, the original objects acquire a new form, a new meaning, and thus a new life. Seen from this point of view, a work of art is not a finished whole; rather, it constantly invites contemplation and reflection, reuse and adaptation. The clearest expression of this idea can be found in the way Van Golden installs his work in exhibitions and in the visual display of his publications. With a rare spatial intuition and endless precision, Van Golden constantly gives his work a new context. His fascination for space is matched by his fascination for the concept of time. In Van Golden’s oeuvre, time does not pass; rather, it constantly repeats itself in a new form. In his work, time is a circular rather than a linear factor. Henny Hagenaars has aptly described this aspect of Van Golden’s method as ‘the visualisation of the concept of time.’ Van Golden himself opted for a more succinct phrase to illustrate his idea: ‘Art is not a contest’, a quote from the poet A. Roland Holst.

Photography is the pre‑eminent medium for expressing in images the passing of time. While the nineteenth‑century photographer Talbot was captivated by the relationship between the photographic image and reality, Daan van Golden’s attraction to the medium lies in the moment that is frozen by the camera. The best representation of this ‘meditative moment of photography’ (Mark Kremers in Kunst & Museumjournaal) is the photo series that derives its name from Oscar Wilde: Youth is an Art. This series consists of over a hundred pictures that Van Golden took of his daughter Diana between 1978 and 1996. With a strong sense for detail, colour, form, meaning and anecdote, he has selected the pictures from his extensive collection and brought them together to form a new whole. Looking at the photos of the growing girl and the constantly changing world around her, the moment – and with that the passing of time – become visible. It is not a smooth progression: some pictures were taken months apart, others a few seconds. Photo sequences are also part of Youth is an Art, such as the ten‑year‑old Diana turning cartwheels in front of a painting by Yves Klein in Insel Hombroich. It is the selection and organisation of what are, after all, snapshots in time that give the series its timelessness. This was guided by various motives, such as contrast and similarity, form and counterform, theme and detail, with chance and coincidence being the decisive factors. Thus two pictures of Diana under the shower in Mahabalipuram (1995) and the picture of Diana on a rock in Mátala (1981) taken fourteen years earlier reinforce each other in form and theme, but also in contrast and similarity. The entire series was exhibited in 1997, but a number of the pictures had – entirely in keeping with Van Golden’s style – been part of exhibitions and catalogues as individual works or in smaller series. The power of Youth is an Art lies in Van Golden’s unconditional love and understanding for a child’s disposition and expression, in the loving glance of a parent on his child without the interference of sentimental or voyeuristic elements.

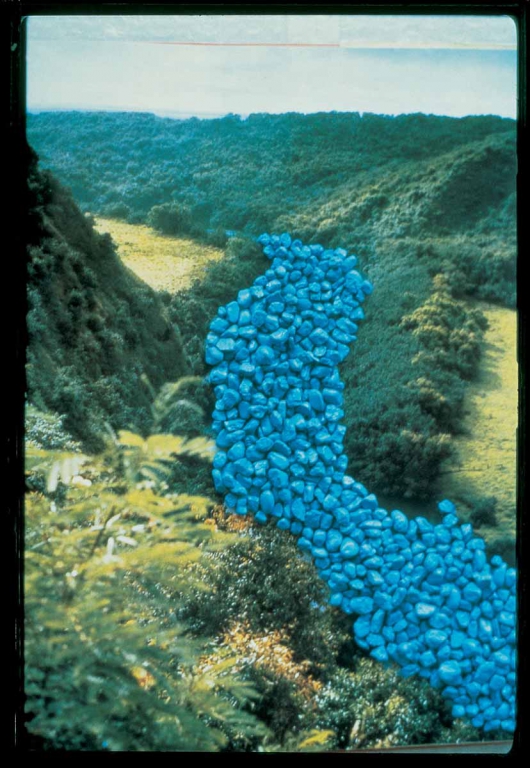

‘Art is the opposite of nature.’ Daan van Golden used this statement by Edvard Munch in his acceptance speech for the PC‑Kunstprijs at Arti en Amicitiae in Amsterdam in 1990. Yet in the project Agua Azul that he created in Amsterdam’s Hortus Botanicus in 1987, art and nature do coincide in a single work. For the duration of Century 87 event, he sprinkled the paths of the Hortus with blue sapphire pebbles. It offered a refined contrast with the plants and flowers that stood like islands in the middle. In Agua Azul, Van Golden managed to create a new beauty with the opposing concepts of art and nature. Although the Hortus has long since been restored to its original state, Agua Azul lives on in the series of photographs that he took of the project. The result is a work with almost abstract photographs in a combination of bright colours, whimsical forms and anthropomorphous shadows. One of the pictures is a self‑portrait of the artist who had registered his own shadow set against the sapphire‑blue background of his own creation. In another picture, the profile of a wood nymph shimmers among the shadows of the trees and the blue gravelled path. In the Hortus Botanicus, with the artist as director, nature had created a new work of art with its own pencil – the camera. Art and nature may be opposing concepts, but if there is one technique in which nature in the broadest possible sense becomes part of the creative process, it is photography. Daan van Golden’s awareness of this is obvious from the uninhibited way in which he approaches his surroundings with a camera. In New Delhi in 1991, he took a homonymous series of photographs of violets, in which the tiny flowers turn out to contain a pattern of smiling faces.

Daan van Golden is representing the Netherlands at this year’s Biennale in Venice. A series of paintings that he made between 1964 and 1998 are on show in Rietveld’s pavilion. The exhibition was brought together by Karel Schampers, curator of modern art at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen and the artist himself. In the catalogue, The Pencil of Nature, Carel Blotkamp, professor of Art History at the Free University of Amsterdam, provides a detailed analysis of the artist and his work. The exhibition here in Amsterdam is mostly a selection from the photo series that Van Golden has made over the last thirty years. Huis Marseille hopes it will serve as a useful complement to the work on display in Venice.

The exhibition Albert Londe was organised in cooperation with the Mission du Patrimoine photographique and the Société française de photographie.