Does a common thread run through the work of the seven photographers who have been brought together for the exhibition A Beautiful Moment? This is not a very easy question to answer. Although the exhibition focuses on a select number of photographers whose origins are all in Japan, the work of each of these photographers is marked by a very personal choice of subject and specific working methods. There does, however, seem to be a certain commonality: namely, the focused and respectful way in which they all approach the medium of photography itself. Their way of looking at the world and of depicting it seems to have its origins in the specifically Japanese sense of beauty that is known in Japanese as wabi sabi: two key concepts from classic Japanese aesthetics that encompass such a wide range of meanings that that they are impossible to translate into a single English equivalent. Wabi has been described as ‘serene attention to simple things’ and sabi as ‘beauty acquired through the patina of time’. In the work of the photographers brought together by A Beautiful Moment the influence of wabi sabi can be seen, for instance, in a profound sensitivity to the various manifestations of nature, and also in an acute attentiveness to the beauty of superficially unremarkable details. However, the exhibition also presents the very opposite of this serene tranquillity: a wild imagination conveying a sense of unease and oppression.

The power of nature

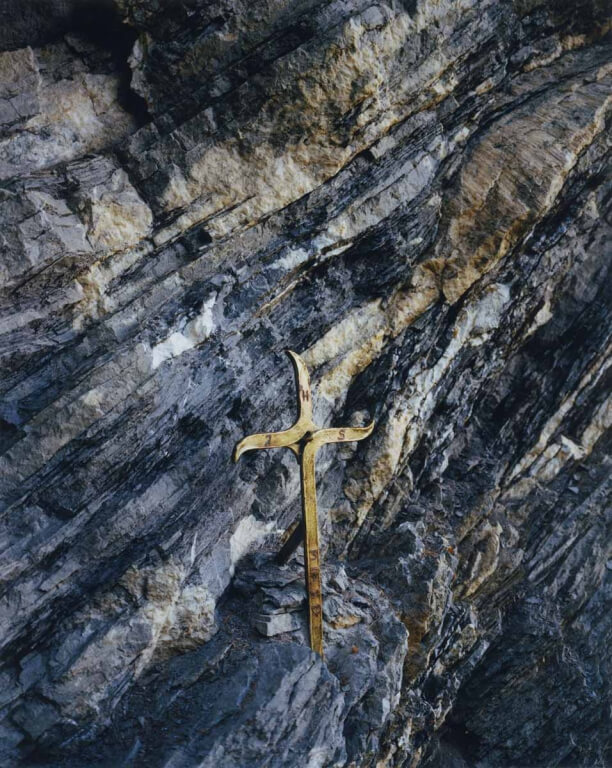

Both the ‘paternal strength’ and ‘maternal generosity’ of water are expressed in the photographs of waves made by Syoin Kajii (Niigata, 1976) off the coast of the island of Sado, the sixth largest island in Japan. As a Buddhist monk and a successor to his grandfather, living in a temple on the coast, he and his digital camera waited for a new ‘face’ in the waves to reveal itself to him. He called this series ‘wave’, Nami (2004). Kajii is not alone in studying the primordial power of nature and the insignificance of humankind: since 1995 Naoya Hatakeyama (1958, Rikuzentakata) has been fascinated by limestone quarries as the setting for a contest of strength between human engineers and a monumental landscape. For a brief moment – for instance, with the help of dynamite – humans can apparently conquer this primordial power, as shown in Hatakeyama’s series Blast. But there is never any doubt about who the boss really is. The ‘human conquest’ in Blast lasts no more than a split second, a brief moment depicted in painstaking detail by the photograph. It has been said of the work of Rinko Kawauchi (1972, Shiga), next, that it is rooted in the Shinto religion. According to Shinto all objects on Earth possess a spirit, and no subject is too trivial to be photographed. In the three series included in this exhibition, Aila (2004), Hanabi (2001) and Utatane (2001), Kawauchi zooms in on the kind of details that usually escape the eye, in photographs that have also been described as ‘visual haikus’. Finally, Nao Tsuda (Kobe, 1976) travels along ancient paths through striking natural landscapes, facing the challenges and dangers of these routes. Tsuda is represented in the exhibition by the mountain landscapes of his series NOAH (2014).

Imagination

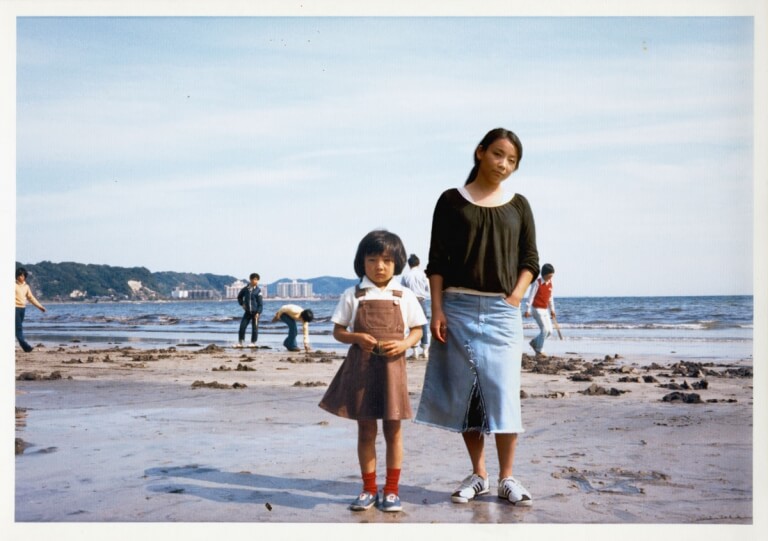

The other dimension explored in this exhibition is that of the imagination of these Japanese photographers: works that have been dreamed, manipulated and constructed. For Imagine Finding Me, Chino Otsuka (Tokyo, 1972) seamlessly joined images of her adult self to those of her childhood self, creating layered images of entirely fictional moments with an unmistakeably melancholic undertone. Yuki Onodera (1962, Tokyo), meanwhile, is fascinated by the way the body, its gestures, its expressions and its movements relate to one another. She does not photograph this relationship directly, however, but evokes it through the experimental techniques she employs in the medium. She manipulates her images, both with the computer and a with variety of printing techniques, creating montages and collages that transform ordinary daily scenes and objects into a visual world of ambiguity and transcendence. A special contribution to the exhibition is provided by the work of the now very aged Toshiko Okanoue (1928, Kochi). Her oeuvre took shape principally between 1950 and 1956, when she created 140 collages based on magazines that the Allied occupation forces had left behind when they withdrew from Japan. Okanoue, whose teenage years were spent in Tokyo, has said in interviews that her creativity gave her hands something else to do besides the ‘sewing, washing, and sweeping’ that she was preordained to perform as a young woman. From her worktable rolled dreamy tableaux that had no point of contact with anything known: collages which mixed Okanoue’s fantasy with her rebellion against the reality of life in postwar Japan. Her images are heavy with a sense both of expectation and of chafing unease.

Japanese photography and Huis Marseille

The work of Naoya Hatakeyama has been part of the Huis Marseille collection since as long ago as 1999. Works by Rinko Kawauchi and Syoin Kajii were acquired in 2004 by the private collector Han Nefkens (H+F Collection) and given to Huis Marseille in permanent loan. Over the following years this ‘Japanese section’ of the collection was expanded, with recent acquisitions of work by Nao Tsuda, Yuki Onodera and Toshiko Okanoue. The exhibition A Beautiful Moment follows Bernd, Hilla and the Others: Photography from Dusseldorf as one of three exhibitions, revolving around key groups of photographs held in Huis Marseille’s own collection, that are being organized in the run-up to the museum’s twentieth anniversary in September 2019. The Huis Marseille collection also contains a significant number of works by the Dutch photographer Jacqueline Hassink, and three photographs that she made in Japan between 2004 and 2014 have also been included in this exhibition.

Featuring work from our collection by

Nao Tsuda, Naoya Hatakeyama, Yuki Onodera, Chino Otsuka, Toshiko Okanoue