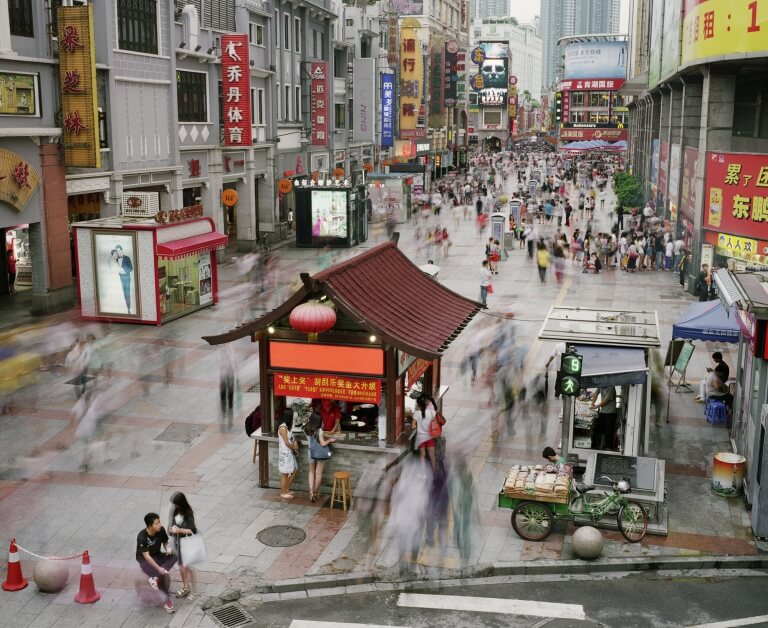

In 2007 the Dutch photographer Martin Roemers started travelling all over the world to photograph ‘megacities’ – those home to over 10 million people – for his project Metropolis. Dynamic streams of movement and static infrastructure determine the composition of his photographs, the image forming a crossroads at which different lives converge. Although the visual identities of places like Mexico City, Guangzhou, Mumbai, New York and Paris are very different, a universal urban image clearly emerges. Martin Roemers recently spoke with Anna Kruyswijk, assistant curator of Huis Marseille, about the documentation of world culture and his fascination with social differences.

Martin Roemers / Metropolis is on display in Huis Marseille from 12 December 2015 till 6 March 2016.

Anna Kruyswijk: What were your criteria in choosing the cities to photograph for Metropolis?

Martin Roemers: The official definition of a ‘megacity’ is one with over 10 million inhabitants. I did some research into the characteristics of these cities, which was what I hoped to find when I visited them. I eventually decided to photograph 22 cities. When I started on this project there were 23 megacities in the world, and now there are 28. There’s no point trying to include them all, because every year there are more of them. China alone has six, and I’ve photographed half of them. The 22 cities I chose give us a representative picture of the megacity.

AK: Cities keep on growing, and the UN has predicted that 70% of the world’s population will be living in a city by 2050. Why is this a good moment to conclude the project?

MR: Having seen all these cities, I don’t expect that future megacities will be remarkably different in character. For instance, the cities of Dakar, Mumbai and Karachi look very similar to outsiders. I can close the project now because the series includes a substantial number of megacities across five continents, and this gives us a good picture of the phenomenon of the megacity.

AK: How did you set to work, from deciding on locations, to choosing the exhibition photographs?

MR: I first looked for a local assistant, preferably a photographer, someone who knew the city well and understood what I was looking for. I also did a lot of my own research into the locations, for example with Google Street View, but I prefer to drive through the city to find locations. I took a week to get to know the city and to make my discoveries. At the most interesting locations I then looked for a high vantage point. I chose a moment when the light was soft to come back to the roof, or the window, or the ladder, to take photographs. I often had to wait for a few hours, or leave and return later, to get the photo I wanted. I worked with analogue photography, so I had to wait for the contact sheets to see what I’d made. Then there was a long selection process to choose the best photos.

AK: And which ones, in your view, are the best photos?

MR: I watched who was coming into the image and who was leaving. When I saw people with something special, I waited for the moment I could get them clearly in view, while keeping a constant eye on the traffic. If everything fell into place, and the frame was well filled, I pressed the shutter. Looking at the pictures later, at home, I always saw new details, however carefully I had been watching everything at the time. I was willing to wait a long time for a location to get busy, but also for chance events. For instance, the rickshaw next to the taxi in Calcutta was an element that I had waited for, but the demonstration in Istanbul was a surprise. So chance played a role, but at the same time I came well prepared and I always knew what I wanted to capture in the photo.

AK: In contrast to the first photograph that Louis Daguerre made of the lively Boulevard du Temple in Paris, your photos show everyone who was there at that moment. After almost two centuries, technology has made so much more possible. What was your technical approach?

MR: I know that Daguerre photo from my student days and the piece has always fascinated me. With Metropolis I am referring to the photography of the late 19th century; I used an analogue camera, a tripod, and long shutter times, just as they did. If I had problems getting access to buildings for the high vantage points I wanted, as in New York and Mexico City, I always had the ladder. My technique boiled down to this: the location, the camera standpoint, and the moment all had to be perfect.

AK: All your photos show us a combination of small and large stories, local matters that go together with a kind of global turmoil. How do the photographs relate to one another in the series, in your view?

MR: Taken together, they show the consequences of this global migration to the city. The differences between the photos result from the characteristics that are specific to each city; the similarities result from the informal economies in which the inhabitants take part, for instance. Newcomers to a city often end up at the edges of society, and those look the same everywhere.

AK: In my experience, your photos are like looking at an ants’ nest through a magnifying glass: they reveal the dynamism and energy of a teeming mass. The visually saturated images report on religion, culture, economics and politics in the heat of the moment. I’m thinking here, for instance, of the protest group in Istanbul that suddenly winds through the photo like a ribbon. Would you agree with this observation?

MR: I’d say that that was an excellent observation!

AK: In 2011 Metropolis won first prize in World Press Photo’s ‘Daily Life’ category. How would you say this series relates to your earlier photo projects, like the one about the abandoned landscape of the Cold War and the one on the life of soldiers in Kabul, Afghanistan?

MR: For me Metropolis is the first step in a new direction. For years I photographed the consequences of war and conflict, but after my most recent project I started looking for a new theme. I’ve travelled a lot, and I’ve been intrigued by cities for years. In 2008 I read a research report by UNFPA, the United Nations Populations Fund, which said that at that moment more than half of the world’s population was living in cities, and I knew what I had to do. For me, this UN report was a reason to photograph the world’s biggest cities: there were developments underway that I wanted to show. My next series will also be more along these lines than my earlier work.

AK: Metropolis mirrors in great detail what all of us are occupied with, and it depicts many of the problems we may face when living in cities in the future. Did you plan to do this?

MR: The city is a theme of our time. Cities have their own problems, naturally, but cities are also solutions to problems. A city is an economy which provides opportunities to build a better life. This series is my reaction to the growth of cities.

AK: How do you feel about chaos yourself?

MR: I live in Delft, so you might say that I obviously don’t care for the bustle of the big city, but my feelings are actually ambivalent. On the one hand I like the small scale and convenience of Delft, but on the other hand I love big cities, and I’d be very happy to live in one. My favourite cities are New York and Mumbai. Both cities do everything at a fast tempo and there’s energy in the air. The people there are ambitious, they want to make progress, and you can really feel it.

AK: Lastly, what would you like to say to those visiting this exhibition?

MR: Look at the photos from a distance. Then go in closer and find all the little stories.

© Huis Marseille and Martin Roemers