The exhibition is a story

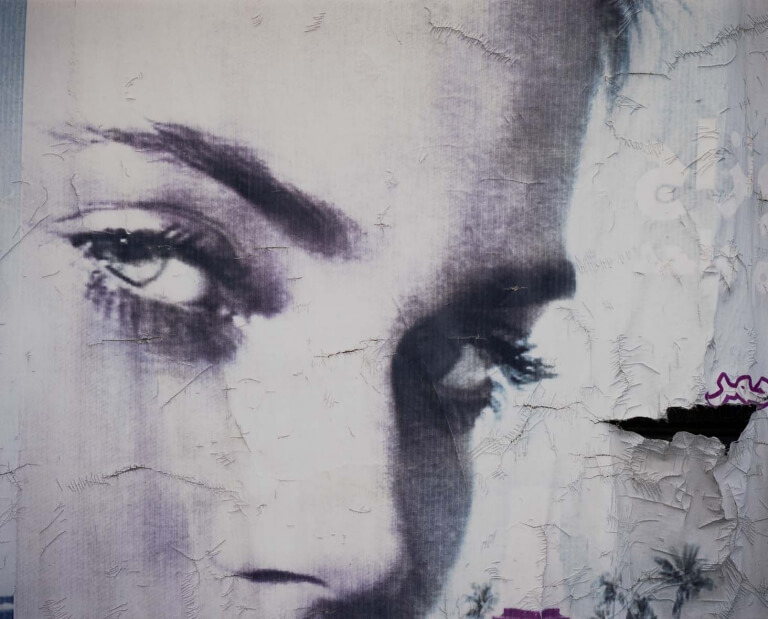

The central figure in Une Femme is composed of different characters. There is Khiar, a handsome, elderly Lebanese gentleman who lives in Beirut, a city scarred by decades of religious tension. The wars that arose from those tensions do not appear in the exhibition, but we sense the presence of an ‘elephant in the room’. Then there is the photographer, who makes images of traffic lights changing, or of the planters that are found everywhere in Beirut, and who finds beauty in a pile of sand or in the banality of a barber’s sign or a grocer’s shop full of food. “I want to make work about ordinary life. I want subtlety, poetry, the gentleness of the banal. I’ve had enough of the spectacular, of what I did when I was working for the New York Times,” says the photographer to Khiar. He wants to transform ugly memories of war into art, and to go from shocking spectacle to silence. We are given no portraits of either protagonist; their presence is evoked by photographs of their surroundings, the marks on an abandoned drinks glass, a glimpse of someone’s back in a plastic chair, or photos of cats. When Khiar shows that he is not interested in having his picture taken, for the photographer their friendship becomes an obsession; he starts photographing hundreds of objects from Khiar’s house. But are these really Khiar’s things? Is the old gentleman in fact an idée-fixe, a composite, the photographer himself, or some sort of alter ego? “C’est le prix à payer pour avoir vécu sur la misère des autres” (That’s the price you pay for having lived off other people’s misery), says Khiar, after the photographer relates a terrible nightmare. Or do these thoughts actually come from his own mind? Une Femme shows that ‘truth’ is irrelevant. Une Femme is an enigmatic and evocative story with a remarkable dénouement. It is also a beautiful exhibition, in which the present and the past are interwoven in Jeroen Robert Kramer’s poetic photographs of Beirut.

Mirror of a prosperous past

After the Second World War Beirut, the capital of Lebanon, became both a tourist destination and a financial hub. The city was dubbed ‘the Paris of the Middle East’ thanks to its French traits and lively cultural and intellectual climate. At that time the country was marked by considerable economic prosperity and a strongly-promoted free market culture. Everything changed in 1975 with the outbreak of a civil war that did not end until 1990. The exhibition includes a series of 35 vintage photos – on loan from the Dutch National Archives – of Beirut before, and just after, the civil war. Though there are certainly signs of the tension surrounding Nasser’s growing political influence in 1958, there is also abundant evidence of a bustling nightlife, thriving shops, and technical progress. These photographs echo contemporary events in the Middle East, as well as entering a dialogue with the atmosphere evoked in Jeroen Robert Kramer’s own photographs.

Documentary: The World According to Monsieur Khiar

In recent years, while he was making Une Femme, Jeroen Robert Kramer was himself being filmed by director Sjors Swierstra and cameraman Erik van Empel. The resulting documentary, The World According to Monsieur Khiar, was selected for the IDFA 2015 documentary festival and had its première there. The Dutch arts programme Het uur van de wolf will broadcast this film at 11pm on Thursday 3 March 2016, on NPO 2 – right before the exhibition opens.

The World According to Monsieur Khiar is a co-production between Memphis Film & Television and the NTR, with support from the Media Fund, the VSB Fund, and the Democracy & Media Foundation. Thanks are also gratefully extended to the Dutch Embassy in Beirut.

The film is 55 minutes long and is screened with English subtitles, starting every full hour in Huis Marseille’s souterrain.

Jeroen Robert Kramer (1967, Amsterdam) lives and works in Beirut, Lebanon. After studying French literature in France, in 2000 he started working in the Middle East as a documentary photographer for Getty Images, de Volkskrant, Der Spiegel, the New York Times, Vanity Fair, and others. His photographs were used in articles on the Middle East, Africa, Afghanistan, Burma (now Myanmar), and the Philippines.

After an unremitting study of life and death in the barren, war-torn Middle East, his work began to reflect his inner struggles with human fallibility, aesthetic constraints, and the harsh perceptions of his profession. In 2008 Kramer decided to stop working as a documentary photographer and in war zones, and to embark on a new, more poetic journey. This led to the book Room 103 (2010), in which images of daily life in the Middle East are intermingled with images of terrible violence. This book won the Dutch Doc Award and the New York Photo Book Festival Award. In 2012 Kramer published the book Beyrouth Objets Trouvés, which in retrospect he regards as a preliminary study for Une Femme.