In March 2024 Huis Marseille will stage the first major retrospective of the American artist Deborah Turbeville (Stoneham, 1932-New York, 2013). The exhibition contains a substantial range of vintage collages, unique works some of which have never been shown before. The unrivalled, dreamy and melancholic shots that Turbeville produced gave a new impulse to photography in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly in the world of fashion. The exhibition Photocollage brings together for the first time images from her most important series, including Bathhouse (1975), École des Beaux-Arts (1977), Unseen Versailles (1982) and Studio St. Petersburg (1995-96).

Unique style

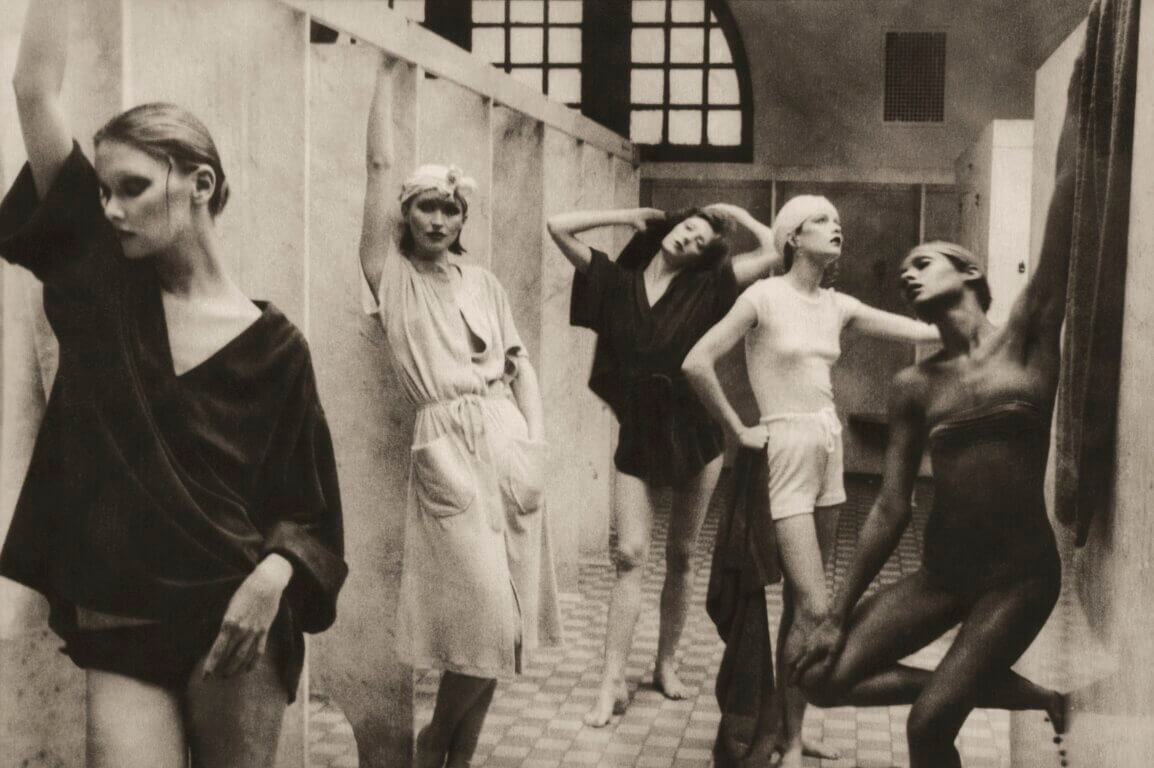

Deborah Turbeville worked primarily for leading fashion magazines and brands, but she expressly did not consider herself a fashion photographer. She had a recognizable style right from the outset in her earliest works dating from the 1970s, with sepia tints that coloured her black and white images, and she used overexposure and a soft focus that veil her subjects. In her work, mysterious female figures pose in public spaces and the interiors of stately buildings, or wander through desolate winter landscapes. The images evoke a dreamworld or a period of long ago and – in the case of her commercial assignments – prioritize the creation of an atmosphere that transcends selling a brand. It is quite common for the garments of the brands for which Turbeville worked to only appear fleetingly in the picture.

As one of the few women in a profession dominated by men, Deborah Turbeville opted to follow a path that was diametrically opposed to that of her colleagues. She searched for models with faces that suggested a rich inner world. In many cases they were people who did not consider themselves to be models and needed some convincing before allowing themselves to be photographed. Turbeville then portrayed them as being lost in thought, in relaxed postures bordering on lethargy – nothing like the modern, sexy and self-assured women who were to be seen in other articles in the same fashion magazines. She wanted to look beyond the models’ outward appearance: ‘I go into a woman’s private world, where you never go,’ she once said.

Photographing, editing, reprinting, merging, pinning

Turbeville’s artistic signature went beyond the photographic process. She continued her experiments in the darkroom in her studio, where the prints were torn, scratched, burnt or taped. Using this process she gave brand new prints a patina, which made the works appear to come from a different age. ‘I destroy the image after I’ve made it,’ she herself said. ’The idea of disintegration is really the core of my work.’ In some images the doubling of the edges reveals a process of repeated working, rephotographing, printing and more working. The upshot is a breathtaking collection of manipulated artworks, torn to pieces and then used to made completely new ones. The exhibition in Huis Marseille brings together authentic vintage prints that are characterized by this extraordinary materiality.

The materiality emerges even better in the collages that Deborah Turbeville made throughout her life. In them, she used T-pins to mount her own photographs on brown paper and she arranged contact prints and notes in the style of storyboards. This gives the works, which are already enchanting in themselves, the character of a film script. But the stories that Turbeville tells remain open and incomplete, like fragments of dreams. The exhibition also includes a broad-based selection of these authentic collages.

The beginning

Photocollage is structured around five themes: ‘The beginning’, ‘Revelations’, ‘Architecture of the past’, ‘Other homes’ and ‘Fictions’. Turbeville’s first collages, works produced on commission and early Polaroids are displayed to reflect the early years of Turbeville’s photographic career. It goes without saying that her best known photoshoot, Bathhouse (1975), is included. This was part of an editorial about swimwear for American Vogue, commissioned by art director Alexander Liberman. The photograph shows five models languidly leaning against the shower walls inside New York’s Asser Levy Bathhouse. This photograph caused considerable controversy. Some readers thought that the women appeared to be drug addicts or lesbians and that the bathhouse looked like the gas chamber of a concentration camp. Turbeville herself said: ‘For me it was just a problem of fitting five girls across a double-page spread.’ The editorial was her breakthrough and Turbeville continued to produce images with an uncanny character during the rest of her career.

Revelations

Turbeville herself said that she had a special gift for finding ‘the odd location, the dismissed face, the eerie atmosphere, the oppressed mood’. This emerges primarily in ‘Revelations’. This part of the exhibition looks at Turbeville’s fashion work after the Bathhouse series, with many commissions that she carried out in Italy and France for the progressive platform Vogue Italia and such brands as Valentino and Comme des Garçons. She made the series École des Beaux-Arts for the latter. Models in the Parisian art academy seem to be in the mysterious space between humankind and classical sculpture. In another series, L’heure entre chien et loup (‘The Twilight Hour’), a gothic aesthetic glimmers with a figure clad in black in the middle of a misty, bare wooded landscape. The city of Venice appears regularly as a setting, which because of its history of decadence and its image full of masks and mystery, dovetails seamlessly with Turbeville’s artistic vision.

Architecture of the past

Turbeville travelled far and wide and had a genuine interest in past architecture, which she depicted in its full crumbling glory. In 1981 Turbeville was commissioned by Jacqueline Onassis (previously Jacqueline Kennedy, then editor at Doubleday) to take photographs inside the Palace of Versailles. Thanks to Onassis’s contacts, Turbeville had access to rooms that were not accessible to tourists. The resulting book, Unseen Versailles, received glowing reviews and earned an American Book Award. Contrary to her earlier work, Turbeville featured few people in her shots. Instead, she depicted sculpture and furniture, in many cases half hidden under dust sheets, in natural light. Newport Remembered (1994) is a continuation of this theme of the decline of monuments to wealth and extravagance. The American Gilded Age (1870-1910) saw the construction in Newport (Rhode Island) of many holiday homes for the nouveau riche who had accumulated their fortunes during the country’s industrialization. During the 1990s Turbeville’s models breathed new life into these meanwhile deserted and neglected mansions. The photographer said: ‘I wanted to take photographs that were outside time, of people in today’s world with the atmosphere of the past reflected in their faces, of palaces and gardens abandoned and overgrown – photographs that retain a history.’

Other homes

Her nomadic lifestyle resulted in Turbeville maintaining homes in several continents: a flat near Pigalle in Paris, a studio in St Petersburg and a historic villa in San Miguel de Allende in Mexico. She always selected residences that were deteriorating to some extent. A friend who supervised the restoration of her Mexican place instructed the workers not to make too good a job of it; ‘the señora likes it that way’. Her series Casa No Name, after the name she had devised for her villa, contains photographs taken in Mexico and Guatemala in special, locally made frames. Her series Studio St. Petersburg (1995-96) features grim-looking buildings and close-ups of faces. Turbeville spent a few months every year for a decade in this Russian city, where the after-effects of the Tsarist Empire were still tangible: ‘I love it because it’s crawling with eccentric artists who are leading secret lives.’ She often referred to 1920s’ Russian filmmakers and such writers as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Gogol as sources of inspiration.

Fictions

Deborah Turbeville started writing a novella at the beginning of the 1980s. Originally entitled A Strange Tale Concerning Ivana P., it was later renamed Passport: Concerning the Disappearance of Alix P. The story is both autofiction and satire and is based on her experiences in the world of fashion. Turbeville became involved in photography quite late. When in her twenties she worked initially as a model and assistant for the fashion designer Claire McCardell and after that for many years she was an editor for Harper’s Bazaar and Mademoiselle. That meant she was well versed in the conventions and limitations of fashion magazines.

The series of collages tells the story of Alix, a designer who is at the top of her game and who recently presented her latest collection to the elite of Paris (including her friend the Empress – for whom Turbeville used a photograph of Diana Vreeland, her friend and mentor who had brought her into Harper’s Bazaar at the time). Passport steers a course between being a film script and a photographic novel. The non-linear narrative uses the form of a series of collages to sketch a disillusioned picture: the pressure of the fashion world takes its toll and Alix struggles with her mental health. For the ending, Turbeville reused photographs from earlier series that she pinned to wrapping paper in her characteristic fashion.

Biography

The photographic career of the American artist Deborah Turbeville (Stoneham, 1932 – New York, 2013) did not really get going until around her fortieth birthday. Previously she had experimented in the 1960s with her Pentax camera in addition to her editorial work at Harper’s Bazaar and later at Mademoiselle. Despite her limited experience, in 1966 she was admitted to the prestigious workshop of photographer Richard Avedon and art director Marvin Israel, who encouraged her to make the move to full-time photography.

Starting in the 1970s, Turbeville was commissioned to photograph advertising campaigns for such fashion houses as Comme des Garçons, Guy Laroche, Charles Jourdan, Calvin Klein, Emanuel Ungaro, Romeo Gigli and Valentino and her fashion shoots were published in fashion magazines like Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Nova, New York Times Magazine and Vogue Italia. Her work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Los Angeles County Museum and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Centre George Pompidou in Paris.

Photocollage

Photocollage was curated by Nathalie Herschdorfer, director of Photo Elysée. The exhibition was produced by Photo Elysée in Lausanne in collaboration with the American MUUS Collection, which purchased the Turbeville estate in 2020.

Photocollage is accompanied by a book of the same name published by Thames & Hudson. It contains essays by Nathalie Herschdorfer, Vince Aletti, Anna Tellgren, Felix Hoffmann, Michael W. Sonnenfeldt and Richard Grosbard and an interview with Carla Sozzani, former editor-in-chief of Vogue Italia. The book is available in the museum shop.

Nathalie Herschdorfer

Nathalie Herschdorfer is director of Photo Elysée in Lausanne. Thanks in part to her former role as director of the Musée des beaux-arts in Le Locle, Herschdorfer has an impressive track record as a curator of photography exhibitions of work by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Stanley Kubrick, Vik Muniz, Viviane Sassen, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Andy Warhol and others. She teaches history of photography at the École cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL) and has written a number of books, including Body: The Photography Book (Thames & Hudson, 2019), Mountains by Magnum Photographers (Prestel, 2019), The Thames & Hudson Dictionary of Photography (Thames & Hudson, 2018), Coming into Fashion: A Century of Photography at Condé Nast (Thames & Hudson, 2012), and Afterwards: Contemporary Photography Confronting the Past (Thames & Hudson, 2011).