In Umkhondo. Tracing Memory Lindokuhle Sobekwa (Johannesburg, 1995) combines existing and new work in order to trace the thematic lines that run through his photographs. His family, his ancestors, and the landscape in which they live on are recurring themes in his oeuvre and form part of Sobekwa’s search for explanations for past events. His moving and intimate work directs the gaze towards his immediate surroundings, to his own identity and to the related larger issues at play in South African society.

Routes along memories

In Xhosa, the photographer’s mother tongue, the word Umkhondo can have many different meanings. It can be ‘tracing’ or ‘tracking’ something, but it can also refer to evidence, a symptom of sickness or a footprint. In the exhibition at Huis Marseille, Sobekwa traces various routes through his own work and connects certain mysterious events, mapping out his own narrative along the way.

This first-ever museum exhibition is the European introduction of a talented young photographer following in the footsteps of great South African names like Santu Mofokeng and David Goldblatt. Like the photographers who have inspired him, Sobekwa critically examines large themes such as race, class, and segregation and approaches them from the perspective of his own experiences and memories, making his work personal and intimate. Photographer and mentor Mikhael Subotzky has called him ‘preternaturally talented’ and admires in his work ‘a vision and a sensitivity that is already uniquely his’. The exhibition offers an overview of all Sobekwa’s projects, which are often long-term and on which he works in alteration. In Huis Marseille each series can be seen as an Umkhondo, a trace on the route.

Autobiographical references

Mthimkhulu III is the first work on show in the exhibition: a tree, several metres high, constructed from torn paper, written texts, photocopies and family portraits, is spreading its branches across the wall of the Bel étage. This autobiographical, site-specific installation refers to Sobekwa’s ancestral clan name uMthimkhulu, which directly translates to ‘the big tree’. After visiting his ancestral home and learning about their cultural connections to trees in relation to a personal family history of migration, he began documenting these ideas in the form of a family tree. In this project, Sobekwa has created a collage using fragmented images of two different trees: one from Johannesburg and one from the Eastern Cape.

The work represents the traces of his ancestors, their names, and the places they have walked. It is an attempt to ‘map’ and document Sobekwa’s family, but also a means of narrating a rich oral family history that has long remained elusive to the artist due to fragmentation, caused by economic and forced migrations.

Personal stories

Lindokuhle Sobekwa belongs to a new generation of South African photographers who were ‘born free’ after the first democratic elections of 1994. He was introduced to photography in high school through the Of Soul and Joy Project in Thokoza, the township in Johannesburg where he grew up, and started by photographing birthday parties and weddings. Later he realised that the medium of photography could be a very important tool to tell stories that concern and interest him.

His very first project, Nyaope (2013-2014), bears witness to this. Named after the eponymous drug – an extremely addictive, cheap variant of heroin – it follows users in Thokoza. ‘I hoped that my images would ignite some kind of conversation in my community about nyaope. The drug has caused a national crisis in South Africa,’ he explains. The emotionally charged, personal black and white images are accompanied by the recent follow-up project Nyaope Chapter II, in which the photographer revisits many of his subjects, exploring various narratives including rehabilitation and ongoing drug use. The project also expands into a participatory approach, with some of his subjects making scrapbooks based on stories they have shared and images he has taken.

Exploring complex relationships

A selection of images from an equally confrontational series is shown opposite Nyaope. For Daleside, Sobekwa photographed the predominantly white community living in this small industrial village on the outskirts of Johannesburg over a five-year period. Years of fascination for, and frustration with the place where his mother had been a domestic worker made him want to understand Daleside for himself. Daleside is both a personal story and a metaphor for the deep-rooted racial divide that still exists in South Africa. Its residents stare directly into the camera, making the distance between the photographer and his subject all the more tangible, and illustrating Sobekwa’s complex relationship with the area.

Breaking the silence

The heart of the exhibition is formed by the video installation I carry Her photo with Me. In a moving slideshow that leafs through a scrapbook of photographs and notes, Sobekwa goes in search of his older sister Ziyanda. She suddenly disappeared at the age of thirteen, and shortly after her return, after having been missing for fifteen years, she passed away.

With the exception of a group photo, from which her face was cut out for the purposes of her funeral, there does not exist a single photograph of her: ‘One day I saw this beautiful light coming in through the window shining on her face. I lifted up the camera to catch the moment and she shot me an evil look and said: “Stop! If you take that picture I’m going to kill you!” So I lowered my camera. I still wish I had taken the shot’. Therefore, Sobekwa goes back in time in I carry Her photo with Me, looking for answers and new memories. He visits people who knew Ziyanda, and tries to reconstruct her life through the places she has been.

The project is a means for Sobekwa to engage both with the memory of his sister and the wider implications of such disappearances — a troubling part of South Africa’s history. The book complements his wider work on fragmentation, poverty and the long-reaching ramifications of apartheid and colonialism across all levels of South African society.

Rooted in the landscape

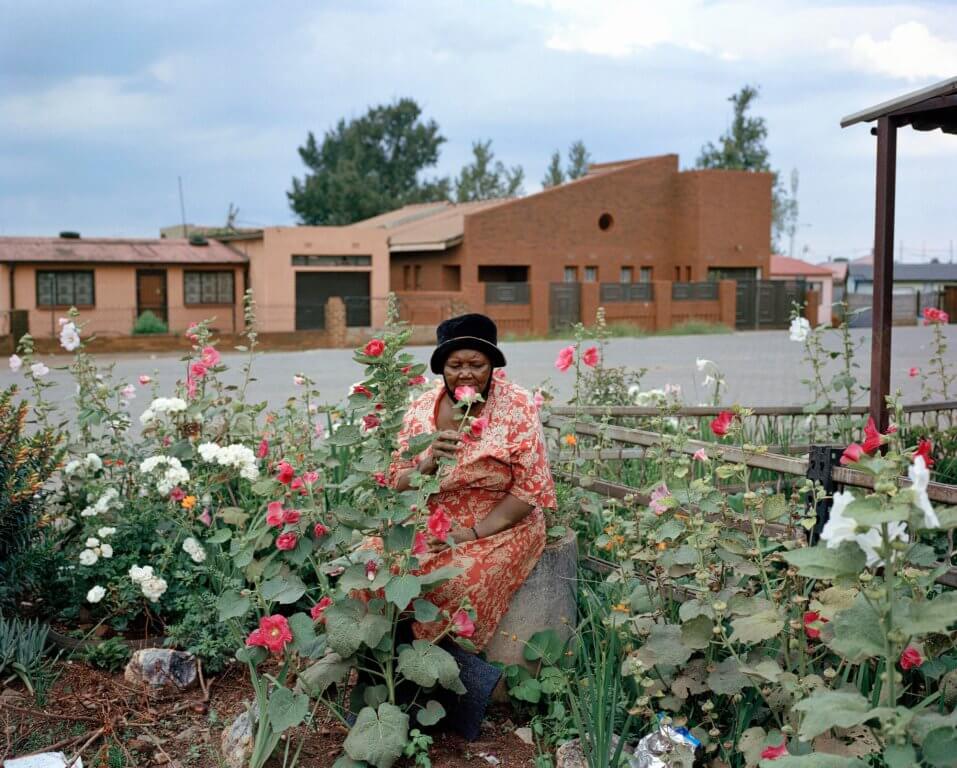

The search for his sister also took Sobekwa outside Johannesburg, to his family and Izinyanya (ancestors) in Transkei, in the Eastern Cape, where Ziyanda spent her childhood and where she is now buried. He continued the series here, photographing the landscape in which she lives on. ‘If you arrive in the countryside early in the morning, you must visit your ancestors,’ he says. ‘Ziyanda is now my ancestor.’ The landscape, with its sacred trees and shrubs, plays an important role in his connection with the ancestors and eventually became the focus of Sobekwa’s most recent series Ezilalini (The Country). As in I carry Her photo with Me, he documents significant places and people in the landscape – this time not in search of a family member, but investigating the horizon that leads him to his own roots.

A narrative of connection and displacement

Sobekwa uses various media and techniques to tell his stories, but his visual language remains recognisable. He effortlessly alternates between black and white and colour, between digital and analogue, and between still and moving images; on most projects, the artist even works simultaneously. It was a new experience for him to create analogue prints of his negatives together with the master printer Peter Svenson in Amsterdam. Although Sobekwa has been working with an analogue camera for years, up until now his photos were always printed digitally. Thanks to the chromogenic development, the colours of the landscape and the people in Ezilalini (The Country) are now revealed as the photographer had always intended.

Throughout the exhibition it becomes clear that Sobekwa’s thematic lines all lead to the same core. His works are a means of examining and interpreting his environment, and with that, himself. It makes his work extremely personal and vulnerable. At the same time, his experiences expose larger themes from South Africa’s turbulent history. Sobekwa’s search for his own family, ancestors, culture and identity is part of a wider reality in which the effects of migration, colonialism and apartheid continue to disrupt and uproot generations to this day.

Lindokuhle Sobekwa (Katlehong, Johannesburg, 1995) started photographing in 2012 through his participation in the Of Soul and Joy Project, an educational programme in Thokoza, a township in the south-east of Johannesburg. During this time he studied with well-known photographers such as Bieke Depoorter, Cyprien Clément-Delmas, Thabiso Sekgala, Tjorven Bruyneel and Kutlwano Moagi. In 2014 the publication of his series Nyaope in several newspapers and magazines brought him international recognition. At the age of 20 he was awarded a grant to study at the Market Photo Workshop. He joined Magnum Photos in 2018, where he became an associate member in 2020. His work has been published in Daleside: Static Dreams, in collaboration with Cyprien Clément-Delmas (Gost Books, 2020) and I carry Her photo with Me (Steidl, forthcoming). He continues to engage with the Of Soul and Joy Project as a mentor, and is mentored by artist Mikhael Subotzky. He lives and works in Johannesburg.

Umkhondo. Tracing Memory is part of Huis Marseille’s summer programme 2022, titled The beauty of the world so heavy, which includes the following exhibitions:

Dirk Kome / Vijf lange meden

Deana Lawson / Collection presentation

Dana Lixenberg / Polaroid 54/59/79

Sabelo Mlangeni / Isivumelwano